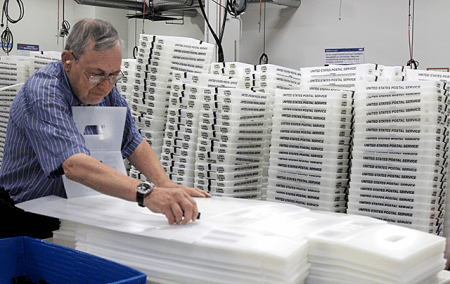

On the main floor of the Minneapolis-based Minnesota Diversified Industries (MDI), Karen Howson is busy arranging piles of flat plastic sheets and transferring them to a nearby production line.

From there, her co-workers fold the sheets and then carefully place them under sonic welding machines to form corrugated plastic mail trays that will eventually go to a large government contract.

In July, Howson will celebrate her second anniversary as a full-time production line worker at MDI, which designs and manufactures plastic totes, trays, boxes and other products for big and small companies, including Amazon, Caribou Coffee, B est Buy and 3M.

est Buy and 3M.

For Howson, who has struggled with anxiety and paranoia for most of her adult life, MDI has given her not just an opportunity to thrive in the workforce for two consecutive years, but also a sense of self-worth. “I love getting up every morning and getting ready to work here,” she said. “It’s given me a lot of purpose in my life and it’s made me really meet goals, stuff that I’ve always wanted to do. It’s really torn down a lot of walls, and I feel very ambitious.”

MDI is a nonprofit organization that was created more than five decades ago to provide people with and without physical, mental or emotional disabilities support services — and opportunities to participate in the labor market.

But in recent years, with the workforce shortage becoming more pronounced in across Minnesota, MDI and other programs that serve people like Howson are starting to notice something new: that more and more employers are turning to people who have disabilities for work. “We’ve seen in the last year and a half an increase in people outsourcing work to us because of the workforce shortage,” said MDI President and CEO Peter McDermott.

Recruiting — and paying well

To meet the growing demand of its customers, MDI — which now has about 320 employees in Minneapolis, Grand Rapids, Hibbing and Cohasset — is looking to expand.

The company plans to do that in two ways: First, it’s working to add 150 more workers to help in its existing production lines. Second, MDI is expanding its services to reach other industries — like the medical sector — which the company has yet to serve.

In addition, MDI is working to train and help more people with disabilities transition into more competitive employment opportunities in traditional companies, like Target and Walgreens.

Workers with disabilities end up at MDI in various ways. Sometimes, like in the case of Howson, a doctor or county case manager refers them to the company, which is well known among organizations that provide services to those with disabilities. Other times, it’s a friend or a temp agency that sends them to MDI.

One reason the company has been so successful in attracting workers, said McDermott, is that it has services that are tailored to people with disabilities. “We have people that are specifically trained to work with them,” he added. “Some people with emotional disabilities might need just a little bit of attention during the workday. It might not be a lot, but enough to get them through the day.”

Another reason people choose MDI is that it pays all of its workers at least the state minimum wage and competitive benefits, including paid time off, life insurance and tuition reimbursement.

That isn’t true for every program that provides employment opportunities to employees with disabilities. Many such initiatives, for example, have subminimum wage certificates, which allow them to pay persons with disabilities below the established minimum wage.

“That’s not us,” McDermott said. “People with disabilities have the same wants and needs as everybody else. They want a high quality of life; they want to live independently; and they want a paycheck.”

A drastic change among business leaders

In Minnesota, there are more than 100 organizations and programs that have long provided individuals with disabilities career counseling and job placement services. Some of these organizations have mainly focused on creating jobs tailored to people with disabilities within their organizations. Others have been working to help such individuals to secure more competitive and integrated employment opportunities in the community.

Vocational Rehabilitation Services (VRS), a state agency with the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, is among the latter. It serves each year about 18,000 people with disabilities throughout Minnesota by providing funding to community partners that offer direct support to people with disabilities.

A large portion of the people VRS serves consist of young individuals, between 18 and 21 years old, who are in high school or in their transition years of service, said Chris McVey, director of strategic initiatives and partnerships at VRS.

“Starting early with people and helping them to identify what they like to do for work and making sure that they have integrated work experiences prior to them leaving school or transition services is a key piece of our work,” she added.

For many years, that meant the agency would go from one employer to another, asking them for job openings that might be a good fit for people with disabilities — opportunities that weren’t often available.

In the last five years, however, McVey said that the agency and most community-based service providers have noticed a drastic change in their interaction with business leaders. Instead of asking employers for job openings, she said, “they’re coming to us and begging for employees” because of the labor market.

While a workforce shortage threatens the overall economic growth, it has forced employers across the nation to look to untapped talent pools, including immigrants, people with criminal records and those with disabilities.

Before she joined MDI in 2016, Howson lived in a group home and struggled to obtain or maintain a permanent job because her employers weren’t prepared to help accommodate her. “My anxiety was really bad,” she said. “So they had to let me go.”

At MDI, Howson said she is “fortunate” to work with supervisors and co-workers who are accepting of her conditions and are willing to help her get through difficult days. In return, Howson and her colleagues are producing professional services for employers who desperately need their skills.

“It’s that kind of compassionate caring that makes me want to come here every day,” she said of her work at MDI. “It gives me purpose.”

Original article published in MinnPost on June 25, 2018 by Ibrahim Hirsi.